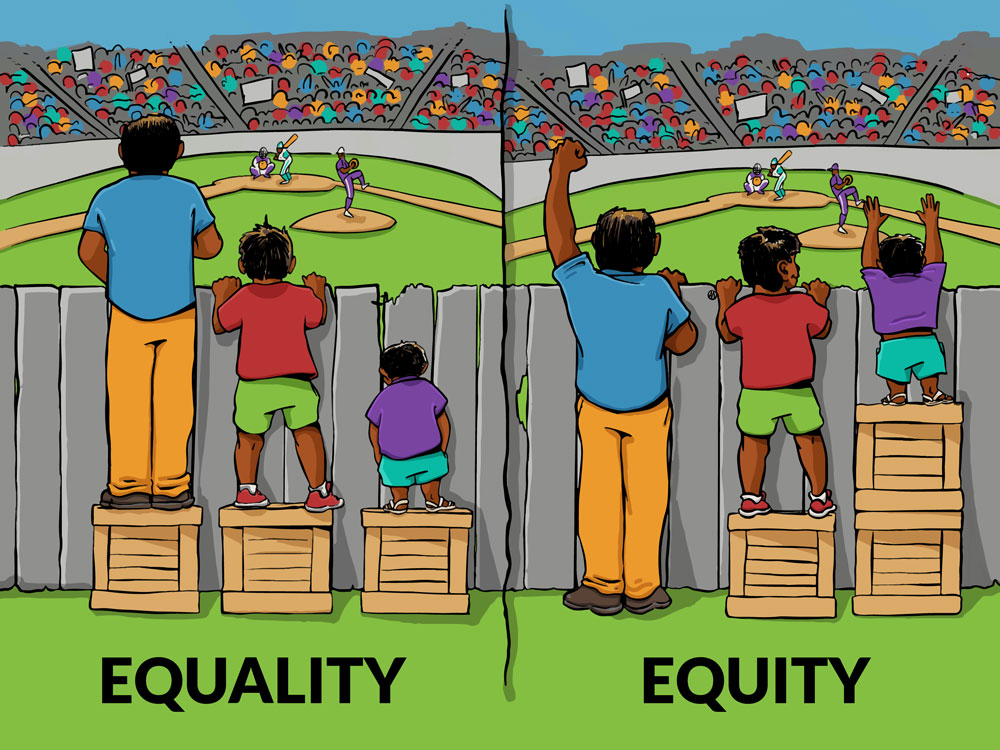

The term social justice is generally used to connote a commitment to redressing social inequalities, such as poverty, racism, misogyny or other human rights issues. Within the field of archaeology, specifically, this means addressing the historical roots of these inequalities – exposing inequalities in the past with the hope of improving the future. Our readings for the week involve archaeology-driven investigations of historical context that explicitly grapple with issues of inequality related to race and class.

Paul Shackel (2007) shares social justice insights gained from the New Philadelphia project, a historical archaeology investigation of a 19th Century integrated frontier town. Shackel (2007, pp. 247-248) suggests that there are four components to archaeological investigation with social justice:

- “(A)rchaeologists need to critically analyze and expose racism in the past and present and to dismantle the structures of oppression where we can.”

- “(W)e need to explore diversity in the past and promote it in the present.”

- “(I)t is important to build a multicultural organization” engaged in archaeological inquiry.

- “(W)e should create a color-conscious rather than a color-blind past.”

His insights are specifically oriented towards race, as this was the most salient research feature of the historical town, but illustrate the general commitments of social justice that can be applied to other themes. Shackel further advocates for a radical transparency of archaeological information. In the New Philadelphia project, they shared all their work on the internet so that community members could see how archaeologists made their conclusions and develop their own interpretations as well.

Paul Mullins (2007) focuses on archaeological projects done in conjunction with communities at large, urban university contexts. His work is concerned with both race and class, and the ways in which land use has changed and disenfranchised communities as neighborhoods were cleared to allow the construction of universities that often catered to students quite different from the people in the surrounding communities.

Mullins (2007, pp. 92) suggests that “rather than aspire to a very specific form of political engagement or community, engaged scholarship might most profitably probe how social groups were marginalized and how specific contemporary discourses reproduce and justify their marginalization.” In this way he also links study of the past with action in the present. By addressing the history of marginalization, archaeologists are uniquely positioned to speak to present inequalities.

What are the particular forms of marginalization or inequality that HCPCP can or should address? How should we address these? Are any of our practices (inadvertently) reproducing these inequalities? As always, please be reflective and critical in your responses.

Bibliography

Mullins, Paul R. (2007) Politics, Inequality, and Engaged Archaeology: Community Archaeology Along the Color Line. In Archaeology as a Tool of Civic Engagement, edited by Barbara J. Little and Paul A. Shackel, pp. 89-108. Alta Mira Press, Lanham, MA.

Shackel, Paul A. (2007) Civic Engagement and Social Justice: Race on the Illinois Frontier. In Archaeology as a Tool of Civic Engagement, edited by Barbara J. Little and Paul A. Shackel, pp. 243-262. Alta Mira Press, Lanham, MA.