Settlement patterns throughout the past 250 years in the Rio Grande Valley have proven to result in the displacement of people of prior communities. When José de Escandón arrived along the banks of the Rio Grande in the mid-1700s with his bands of Spanish colonial settlers to claim the land for the King of Spain, Native American peoples who occupied the region were either displaced or had to assimilate into the life-ways of the new arrivals. One hundred years later, as a result of the American victory in the war with Mexico, ‘Anglo’, or white/non-Hispanic settlers embarked upon the opportunity to acquire a lot of land for little money. At first, many of the newcomers would marry into the Tejano or Mexican-Texan community in order to accumulate wealth and function successfully in the local business community, but eventually, many Anglo settlers would attempt to marginalize the local population by taking over large portions of land that was lost by the heirs of the original Spanish land grantees. With the turn of the 20th century and the installation of the railroad to the Rio Grande Valley, more and more Anglo Americans arrived; attracted to the promise of guaranteed success in farming in the ‘Magic Valley’.

As towns began to emerge along the railroad tracks that ran between Harlingen and Mission, marginalization of the local Hispanic communities became more evident. With land developers building Anglo communities that contained larger lots on the south side of the railroad tracks, the Hispanic population was displaced to smaller lots on the north side of the tracks. Even though the Anglo population was technically the minority population in terms of numbers, somehow they had the power to dictate exactly where the Hispanics could not go to school, where they could not shop and where they could not socialize. So, with each new wave of settlers that has chosen to move to the Rio Grande Valley, displacement of the previous population has occurred. However, fast forward another 100 years to the mid-20th century and you will see a movement of leadership in the Rio Grande Valley shift as Hispanic leaders such as Hector P. Garcia founder of the American G.I. Forum, Raul Yzaguirre of the National Council of La Raza and the Civil Rights movement, and especially in municipal politics where there were several mayors emerged in towns throughout the Valley with Hispanic surnames (e.g., Alfonso Ramirez elected 1st Hispanic mayor of Edinburg in 1963).

I apologize for the long introduction about my theory of marginalization throughout Rio Grande Valley history but I feel it is important to identify trends. The question this week asks us about forms of marginalization or inequality with regard to the HCPCP. The theories at work here are that those who are buried in this Hidalgo County Pauper Cemetery are either from the indigent or low income population, or had no family to claim them at their time of death. In a sense, marginalized because either no one could pay or no one cared. Was this potter’s field initiated in an effort to segregate and marginalize? According to research done for Cemeteries of Texas, this cemetery was appropriated in December of 1913 by the Edinburg Cemetery Association via trustees James H. Edwards, Washington Barton and Plutarco de la Viña. Burials took place in this cemetery between 1913 and 1990. The property as a whole contains four cemeteries. The Restlawn section of the cemetery is the most segregated portion; located in the far, north-westernmost point of the grounds. Mirroring a point in time in Edinburg where schools were segregated as White only, Mexican, and Black, the cemetery system within the Hidalgo County seat appears to be no different.

In the Mullins article, he refers to marginalized communities found on college campuses with respect to archaeological civic engagement projects and urban renewal (92). The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV) is one of the largest and most recognized Hispanic-serving institutions in the country. I would like to think that the Hispanic community is not marginalized within the walls of this institution nor within the communities at large. As promoted in Shackel’s article, HCPCP is following along the same effort to ‘foster dialogue’ that examines the inequities of society with hopes to bring about a social consciousness (243). We are following this directive by making an effort to engage the local citizens in the scope of this project simply by initiating it. We are examining, recording and analyzing the make-up of this cemetery as a whole.

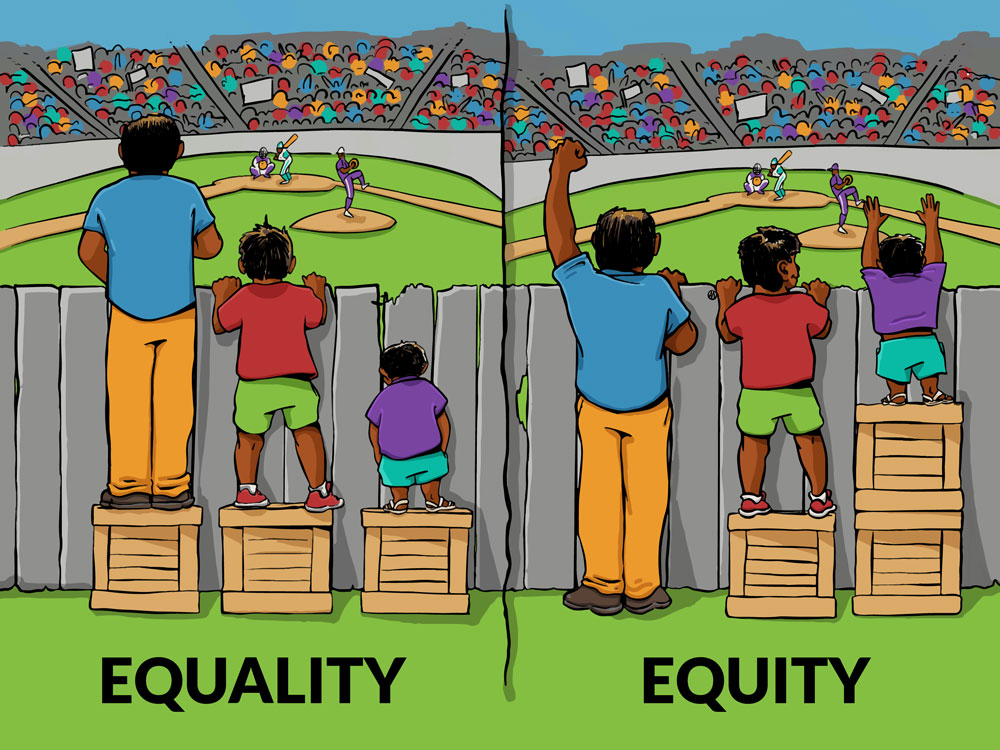

The students in our class have been collecting data on the gravesites within this cemetery and have found a majority of Hispanic surnames among the buried. Should we equate poverty with the term “Hispanic” as a result? What is interesting about the term ‘Hispanic’ is that there is a constant reference to this being a minority group in this country. I think that it is time to stop using the word ‘minority’ with relation to the word ‘Hispanic’. I know one very strong-minded person who is Hispanic and refuses to be referred to as a ‘minority’ because ‘minority’ means ‘less than’ and no one should feel that he/she is less than anybody else. In fact, the Hispanic population has become the majority in our country. Perhaps someday in the future there will be so much blending of the three biological races (as well as multi-cultural blending) that it will be difficult to clearly identify a person as purely Caucasian, Mongolian or Negroid. So, if we as a society continue to produce inequities among biological races, cultural groups, religious groups or socio-economic groups, then we need to practice more acceptance and understanding than prejudice and exclusion. We cannot change the past, but we can chose to behave in a more tolerable and less fearful manner in order to foster positive change.