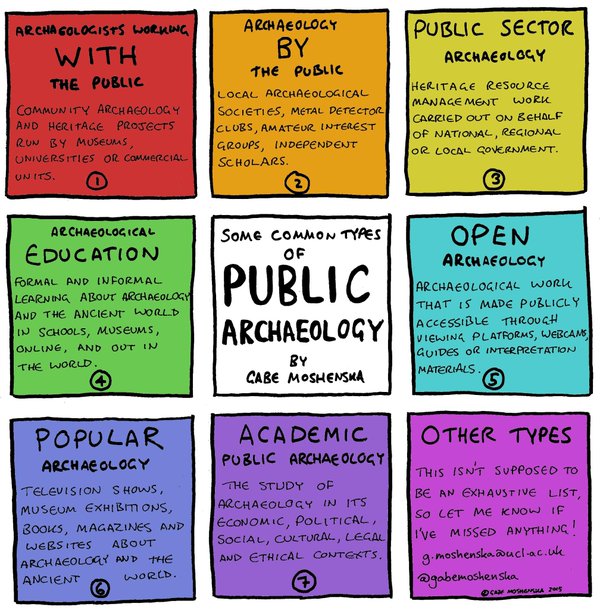

Public archaeology is both a field of study and a body of practice that integrates and prioritizes engagement with non-specialists in the development, conduct, and dissemination of archaeological projects and information. As such, it encompasses a wide variety of activities. Gabe Moshenska has proposed seven common types of public archaeology, while acknowledging that more variations exist.

The project we are about to undertake arguably falls across several of these categories. We are archaeologists looking to work with the public (category 1), aligned with educational goals (category 4), sharing our work publicly through digital medium (category 5), while also being critical and reflexive about the work we do (category 7). This sort of spread across multiple categories is not uncommon for public archaeology projects.

Public archaeology also exists as an umbrella term that can encompass such practices as community archaeology, collaborative archaeology, decolonial archaeology, and indigenous archaeology, though each of these terms have their own literature and speceficities.

The article that we read for this week (Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez 2015) provided a nice review of different categories of public archaeology that have been proposed by researchers in the past. They emphasize the importance of understanding the various publics involved in a project, something we will explore in greater detail in our “Stakeholder” week.

The article further explores the ethical implications of conducting public archaeology, and the responsibilities that archaeologists have to try do things in an informed and deliberate way:

“Everybody feels ready to conduct public archaeology, but it must be planned and designed as are other facets of the archaeological project…The wrong approach might lead to negative feelings towards archaeology (or archaeologists), incorrect information about our work disseminated to the public or political and social conflict leading to the destruction of archaeological sites” (Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez 2015, p. 204).

“We desperately need archaeologists interested in the public, but also professional public archaeologists” (Richardson and Almansa-Sánchez 2015, p. 205).

The issues presented in the article preview many of the themes that we will address as the semester progresses. We must be thoughtful about the work we do, but also flexible and inventive. Public archaeology is rarely predictable, but it is always an adventure!

The question of the week is: What is public archaeology to you? How does our project align with this? What lines of investigation are you interested in pursuing?